You’ve just got to read more of a book that has this as its opening line:

You’ve just got to read more of a book that has this as its opening line:

Hayden Griffin was plucking a fish when the gravity bell rang.

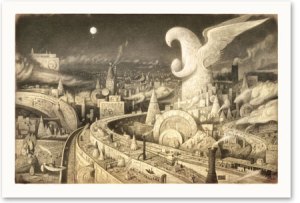

The rest of Karl Schroeder’s Sun of Suns lives up to the promise delivered in the first line, at least in the setting department. Hayden Griffin’s world is a giant bag of gas with a fusion reactor at the center to give light. Cities are wheels that spin for local gravity so that people’s bones don’t degenerate. People hunt for flying fish in nearby clouds and farm on clumps of dirt caught in nets. Cue lots of airship travel and zero-g aerial battles. Oh, and outside the giant gasbag? It’s a post-singularity far-future SF that’s only being kept at bay because the fusion reactor scrambles electronics.

In short, the setting of Sun of Suns is exotic, cool, and creative. Everything else about the book is … well, okay. The plot: Hayden Griffin is out for revenge against an admiral who ordered an attack on his home city. The characters: I’m not buying Hayden’s rather sudden character growth at the end. It feels like Schroeder deliberately put dimensionality into his characters rather than letting it grow. And somehow he manages to make sky pirates not awesome. They are also okay.

Overall, Sun of Suns reminds me of Larry Niven’s Integral Trees, but better. Integral Trees had a really cool setting with characters you don’t care a whit about. Sun of Suns has a really cool setting with characters you can kinda sorta care about. Plus, it’s the first book in a trilogy, so maybe Hayden and his friends will get more interesting as the story develops.