Thanks to the positive response my last post got, I’ve put the source code for The Layers of English up on GitHub. You can find it here:

Tag Archives: etymology

The Layers of English – Anglo-Saxon, French, Latin

The English language is a wonderful mess. After centuries where England got invaded by Romans*, Angles, Saxons, Vikings, and Normans, and then the nineteenth century where the English turned around and colonized one quarter of Earth’s landmass, the language has words from all over the world. English speakers seem to love picking up everybody else’s words whenever we come into contact with them.

English words come from three main sources. The oldest are the Germanic words from the Angles, Saxons, and the Vikings. The words that make up the nuts and bolts of the language like “the,” “of,” “and,” and “with” are Germanic. In 1066 Normans invaded and brought Old French with them, which evolved into words like “cuisine,” “gallant,” and “herald.” Meanwhile Latin and Greek were the languages of educated people throughout the Middle Ages and their words migrated into English in scientific and technical contexts. Words like these include “phosphorylation” and “poikilotherm.” This migration is still happening today as scientists are in the habit of stringing Greek and Latin roots together to name new ideas.

You, as a writer, can exploit the layers of English to control how your work sounds. You can dial up the register, towards Latin and Greek, to sound cool and cerebral. Or you can dial it back to the German end to sound gutsy and raw.

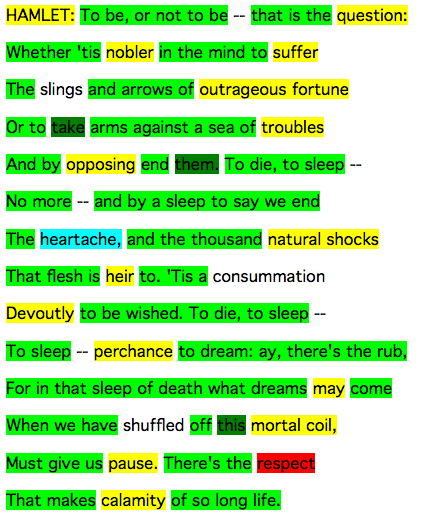

I wrote a computer program that lets you visualize how this works. It color codes text based on word origins.

All the texts I ran through the program are more than half Anglo-Saxon and Germanic. These words make up the core of the English language. Note how Dr. Seuss and Shakespeare run to the Germanic end, the political and scientific texts are more French, and the scientific paper is a whopping eight percent Greek and Latin words.

You can use this tool to see where a writer makes a shift in register as well.

I’d eventually like to make this program a Web app. In the meantime, send me a text you like and I’ll analyze it.

* A Redditor pointed out to me that the people living in the area at the time the Romans invaded spoke Celtic languages, which aren’t closely related to English, so the Roman invasion wouldn’t have had that much of an effect on English evolution.

TECHNICAL STUFF

This code is written in Python. I’m new to programming, so I learned a lot while writing it – about dictionaries, variable scope, JSON, and regex.

I used word lists on Wikipedia to make an etymology dictionary. Then I wrote a script that reads in the text, looks it up in the dictionary, then adds HTML tags based on the word’s etymology. It outputs an HTML file.

I handled Greek words a bit differently, since there is no definitive list of English words with Greek roots. I made a list of Greek roots (again from Wikipedia). If no other etymology can be found, the script searches for Greek roots within a word. As you can see, this leads to some false positives. Furberg, a Norwegian last name, got marked Greek because it has the letters “erg” inside it.

I checked the program on the Ten Hundred Most Used Words that were inspired by Randall Munroe and reprinted by Theo Sanderson. I took the words that the program had missed and manually looked them up on the Online Etymology Dictionary, then added them to my dictionary’s vocabulary. I wanted even more vocabulary, so I ran the program again on the first five thousand of this list of the twenty thousand most common words online. Then I went back and manually added more words.

I added Arabic etymology because “coffee” showed up in the Ten Hundred Most Used Words list, and I like coffee.

I’d be happy to share my code and I would love a code critique.

Text sources:

The Gettysburg Address

Hamlet’s Soliloquy

Hop on Pop

The United Nations Declaration of Human Rights

A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid