Thanks to the positive response my last post got, I’ve put the source code for The Layers of English up on GitHub. You can find it here:

The Layers of English – Anglo-Saxon, French, Latin

The English language is a wonderful mess. After centuries where England got invaded by Romans*, Angles, Saxons, Vikings, and Normans, and then the nineteenth century where the English turned around and colonized one quarter of Earth’s landmass, the language has words from all over the world. English speakers seem to love picking up everybody else’s words whenever we come into contact with them.

English words come from three main sources. The oldest are the Germanic words from the Angles, Saxons, and the Vikings. The words that make up the nuts and bolts of the language like “the,” “of,” “and,” and “with” are Germanic. In 1066 Normans invaded and brought Old French with them, which evolved into words like “cuisine,” “gallant,” and “herald.” Meanwhile Latin and Greek were the languages of educated people throughout the Middle Ages and their words migrated into English in scientific and technical contexts. Words like these include “phosphorylation” and “poikilotherm.” This migration is still happening today as scientists are in the habit of stringing Greek and Latin roots together to name new ideas.

You, as a writer, can exploit the layers of English to control how your work sounds. You can dial up the register, towards Latin and Greek, to sound cool and cerebral. Or you can dial it back to the German end to sound gutsy and raw.

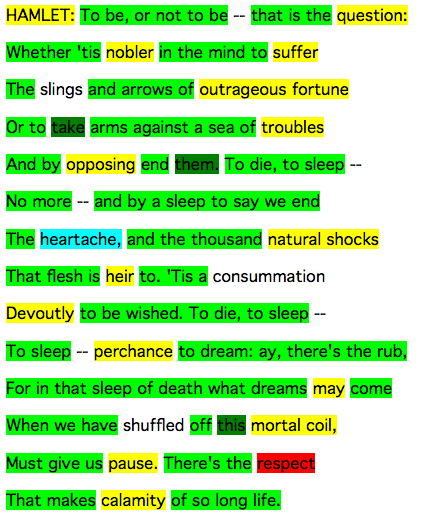

I wrote a computer program that lets you visualize how this works. It color codes text based on word origins.

All the texts I ran through the program are more than half Anglo-Saxon and Germanic. These words make up the core of the English language. Note how Dr. Seuss and Shakespeare run to the Germanic end, the political and scientific texts are more French, and the scientific paper is a whopping eight percent Greek and Latin words.

You can use this tool to see where a writer makes a shift in register as well.

I’d eventually like to make this program a Web app. In the meantime, send me a text you like and I’ll analyze it.

* A Redditor pointed out to me that the people living in the area at the time the Romans invaded spoke Celtic languages, which aren’t closely related to English, so the Roman invasion wouldn’t have had that much of an effect on English evolution.

TECHNICAL STUFF

This code is written in Python. I’m new to programming, so I learned a lot while writing it – about dictionaries, variable scope, JSON, and regex.

I used word lists on Wikipedia to make an etymology dictionary. Then I wrote a script that reads in the text, looks it up in the dictionary, then adds HTML tags based on the word’s etymology. It outputs an HTML file.

I handled Greek words a bit differently, since there is no definitive list of English words with Greek roots. I made a list of Greek roots (again from Wikipedia). If no other etymology can be found, the script searches for Greek roots within a word. As you can see, this leads to some false positives. Furberg, a Norwegian last name, got marked Greek because it has the letters “erg” inside it.

I checked the program on the Ten Hundred Most Used Words that were inspired by Randall Munroe and reprinted by Theo Sanderson. I took the words that the program had missed and manually looked them up on the Online Etymology Dictionary, then added them to my dictionary’s vocabulary. I wanted even more vocabulary, so I ran the program again on the first five thousand of this list of the twenty thousand most common words online. Then I went back and manually added more words.

I added Arabic etymology because “coffee” showed up in the Ten Hundred Most Used Words list, and I like coffee.

I’d be happy to share my code and I would love a code critique.

Text sources:

The Gettysburg Address

Hamlet’s Soliloquy

Hop on Pop

The United Nations Declaration of Human Rights

A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid

Ancillary Justice by Ann Leckie

The main character is a spaceship. And she is hell bent on revenge.

It is not the plot that makes Ancillary Justice by Ann Leckie shine – the above is all there is to know about it. Nor is it the setting, which is standard space opera fare. It’s the technical mastery it takes to write a first-person novel from the point of view of an AI hive mind. In some of the early chapters Leckie writes from the first person omniscient. I didn’t even know you could do that. Look:

“Is she coming or not? If she isn’t coming she should say so.”

At that moment Lieutenant Awn was in the bath, and I was attending her. I could have told the lieutenants that Lieutenant Awn would be there soon, but I said nothing, only noted the levels and temperature of the tea in the black glass bowls various lieutenants held, and continued to lay out breakfast plates.

Near my own weapons storage, I cleaned my twenty guns, so I could stow them, along with their ammunition. In each of my lieutenants’ quarters I stripped the linen from their beds. The officers of Amaat, Toren, Etrepa, and Bo were all well into breakfast, chattering, lively. The captain ate with the decade commanders, a quieter, more sober conversation. One of my shuttles approached me, four Bo lieutenants returning from leave, strapped into their seats, unconscious. They would be unhappy when they woke.

Justice of Toren/One Esk Nineteen/Breq has a bizarre sense of identity. In the first half of the book, every other chapter describes the backstory, in which the Justice of Toren is a battleship crewed by dozens of officers and running her software in the brains of hundreds of meat-puppet human bodies. In the present day, the Justice of Toren has all been destroyed save for one puppet body. She still thinks of herself as a spaceship. And she thinks of herself as having already been murdered.

What the hell is Justice of Toren/One Esk Nineteen/Breq? She’s AI software running on a human brain. To make things even weirder, another character points out that it’s probably possible to bring back her body’s original owner (some nameless political prisoner). And her remaining body earns command of a ship, so now she’s a spaceship inside a human inside a spaceship.

A lot of the philosophical parts of the book explore what happens when a mind becomes divided against itself. This doesn’t just apply to the spaceship characters.

On the other hand, there’s so much philosophy in the book that not much happens. Add to that a nonlinear plot, an unreliable narrator, and characters who like to talk around the point in a way that would make Jane Austen proud, and you have yourself a tough read. I recommend looking up all the spoilers online first so you can know what’s going on. Then you can sit back and enjoy the thought experiment.

Franconia Sculpture Park

I went to a wedding at the Franconia Sculpture Park last week.

Wild Seed by Octavia Butler

I’ve kept hearing Octavia Butler’s stuff is really good. I only waited this long to read something of hers because I didn’t know where to start. Butler broke into print in 1976 with Patternmaster then wrote successive prequels to it. Wild Seed is the earliest in the sequence of events and regarded by John Pfeiffer as the best book she ever wrote.

The language of this book struck me right away. Check out this passage near the beginning:

Anyanwu looked away, spoke woodenly. ‘It is better to be a master than to be a slave.’ Her husband at the time of the migration had said that. He had seen himelf becoming a great man – master of a large household with many wives, children and slaves. Anyanwu, on the other hand, had been a slave twice in her life and had escaped only by changing her identity completely and finding a husband in a different town. She knew some people were masters and some were slaves. That was the way it had always been. But her own experience taught her to hate slavery. She had even found it difficult to be a good wife in her most recent years because of the way a woman must bow her head and be subject to her husband. It was better to be as she was – a priestess who spoke with the voice of a god and was feared and obeyed. But what was that? She had become a kind of master herself. ‘Sometimes, one must become a master to avoid being a slave,’ she said softly.

I think I count a dozen words in that entire paragraph with French or Latin origins. The rest of it is Ango-Saxon, emotional and gritty. She introduces complex ideas about slavery, gender, dominance and submission with deceptively simple language. And she keeps it up this way for an entire novel.

Wild Seed is also about game theory, since Anyanwu is trapped in a game with Doro she can’t win. And it’s about our relationship with our bodies, since Anyanwu’s super power is her body and Doro has no body at all. He’s fascinated with breeding human beings to each other because he’s impotent. The book is everything N. K. Jemisin was trying to cover with The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms, but Octavia Butler is a master at it. The book will make you think. A lot of it you’ll wish you weren’t eating lunch while you were reading.

Wild Seed feels like an epic love story even though it’s a fairly short book. The ending was abrupt, especially for me, because my edition includes a big chunk of Mind of my Mind. I got three quarters of the way through the book, saw the end, and had to page backward looking for a climax.

Other issues include that you can tell it’s a prequel. Many aspects of the psychic humans are really only in there because of the psychics later in the series. And Doro’s breeding program has a surprising lack of Asian people considering that a) most people in the world are Asian and b) Doro’s willing to take advantage of all the genetic material he can get. But these are quibbles. This is a beautiful, thought-provoking, challenging book.

A Fire Upon the Deep by Vernor Vinge

A Fire Upon the Deep is two books, really. One book is a space opera in which Ravna Bergensdot and Pham Nuwen race to find a cure for the Blight. The other book is a work of xenofiction in which the only cure for the Blight crash lands on a planet of hive-mind ratdogs.

Space opera just isn’t my bag, so I found myself slogging through those parts to get to the xenofiction parts. There’s nothing especially wrong with it, Ravna and Pham are nice enough, but it’s all stuff you’ve seen before if you have a passing knowledge of science fiction.

But the ratdogs! (They just call themselves people, but a girl who crashes on their planet nicknames them Tines.) There isn’t enough xenofiction out there and the work Vinge has done with the Tines is top notch. Each individual person is made out of four to six creatures that communicate by ultrasound. Vinge thinks through a lot of the implications, like the naming conventions, what happens when two of the major characters get each other pregnant, and what it’s like to see through six pairs of eyes at once.

One of the most interesting parts is the Tines’ relationship with identity. Each group person can accomplish something like immortality by pulling a careful Ship of Theseus. They make themselves bigger by giving birth, and they make new people by splitting in half or splicing together bits of themselves and their friends. They fear becoming unrecognizable like we fear death. Vinge pulled off a work of hard science fiction where souls are very much a part of daily life.

The book’s full of wonderful ideas. None of the characters are especially strong, though the Tine characters make up for it by being so damn cool. The ending relies on a lot of coincidences to get all the characters onto the same stage at the same time. I would have rather Ravna and Pham had landed on the Tines’ world early on and raced to stop the Blight on the ground. Even better if Vinge had dispensed with the space opera entirely and written a book about the Tines’ political intrigues, Watership Down style.

I have a nitpick about Pham Nuwen’s almost but not quite Earth name. He’s clearly supposed to be Pham Nguyen because he’s described as a living fossil (hard vacuum mummification accident), derived from an Asian culture, and nobody can pronounce his last name to save their lives. So why not just call him Pham Nguyen? The slightly-offness of his name makes by brain itch.

The Tines are so cool that this book’s worth reading on their strength alone.

Scientists Looking at Liquid

This all started because I saw an ad on the back of a magazine. The ad was for a DNA assembling machine and featured a woman looking at a tiny vial of amber liquid, which seemed oddly specific. Where could a biotech company get such a picture? Vu was there and he said it was probably a stock photo. Pictures of scientists looking at liquid are everywhere.

So I checked.

Pictures of scientists looking at liquid are everywhere. These are some of my favorites from a Google image search for “scientist:”

The only thing we seem to like half as much as looking at liquid is looking at microscopes. But that’s a distant second. Looking at liquid is definitely the favorite. Especially if it’s green.

Do you guys have any favorite pictures of scientists looking at liquid? Could you please share them with me?

Blue Monday by Orkestra Obsolete

Kushiel’s Dart by Jacqueline Carey

In an alternate history Europe, Mary Magdalene and Christ have a child by magic. Their son Elua wanders the earth with some fallen angel disciples, preaching free love, and eventually settles in alternate France. The religions of this Europe are a mishmash of free-love-utopia, paganism, and regular Christianity, whose followers live in the “Yeshuite Quarter” of the city and are mistrusted at best.

Phèdre, a holy prostitute in training, gets the opportunity one day to also become a spy. Clients talk when they let their guards down. This book is her bildungsroman.

It takes a long time to get going. I recommend you muscle through the first few dozen pages or so until Phèdre starts plying her trade for real. It gets better.

The book’s at its best when Carey examines what a free-love-utopia might actually look like. She handles the touchy subject of prostitution with subtletly. The practice isn’t glorified or vilified. It’s a career, with all the day-to-day gripes that go with it.

Carey has the fortitude to poke her notion of utopia full of holes, too. Do the characters really “love as they wilt,” as Elua commands them to? How willingly taken is the vow of sacred prostitution when the prostitutes are sold into the temple’s service at a very young age? What about the nobility, who have to marry for political reasons? What happens if people with incompatible sexualities fall in love with each other?

The sex didn’t shock me. It did send my eyes rolling sometimes. No, they wouldn’t have been able to do that. Not that many times in one evening! Other characters get pregnant by accident, but not Phèdre for some reason, and STDs are mysteriously nowhere to be seen.

The alternate history aspect of the novel was a mixed bag for me. On the one hand, a magical being controls the English Channel and doesn’t let most people through. An alternate Britain that never had a Norman Conquest is pretty cool. You’re thrown into a world that’s halfway between Beowulf and the Mabinogion yet strong enough to be an (almost) equal partner to alternate France.

But alternate Germany didn’t make any sense. That region of Europe in our world has been alternately impressing or terrifying its neighbors with technology since the Renaissance. It brought us the printing press, modern chemistry, and rocket science and in Phèdre’s world they’ve been reduced to Orcs. The only reason they present any threat at all to France is they found a leader with two brain cells to rub together and there are a lot of them. The changes to Britain make sense because of the isolation, but there’s no explanation given for the Germans.

Worse, the book can tread into some pretty unfortunate territory. The D’angeline (French) people are inherently more awesome than their neighbors because of their ethnic background, which contains angel blood. It gets to the point where the German savages are awestruck by Phèdre and her companion just by looking at them. Phèdre describes non-D’angeline people as “like children” on two separate occasions.

Should you read this book? If it’s your thing, sure. If it’s not, don’t worry about it.

The Writer’s Mary Sue Test by Kat Feete

Mary Sue is a problem that tends to happen when we writers are just starting to learn the craft. A writer wants to make a character AWESOME, but she doesn’t know how to do it, so she slaps a bunch of AWESOME characteristics onto the character, like an unusual hair color, a dark and troubled past, unbeatable fighting skills. And the AWESOME character starts to look suspiciously like the writer herself…

Kate Feete wrote an insightful quiz to determine whether you are getting too personally invested in a particular character. Check out her analysis of the Mary Sue phenomenon after the quiz, too.